Shawn Evans, AIA, Atkin Olshin Schade Architects

Center City Philadelphia was home to the region’s most well known movie theatres. Clustered in districts on Market, Chestnut, South, and North 8th Streets, these entertainment venues lined up along the sidewalks with blinking lights and glistening facades to draw in thousands of visitors to downtown. An earlier blog post, “Historic Movie Theatres of Center City Philadelphia,” chronicled some of these places that are documented in the photograph collections of the Philadelphia City Archives. Whereas downtown movies were for most people a special treat, the neighborhood theatres were a more integral part of weekly life. [i]

WEST PHILADELPHIA

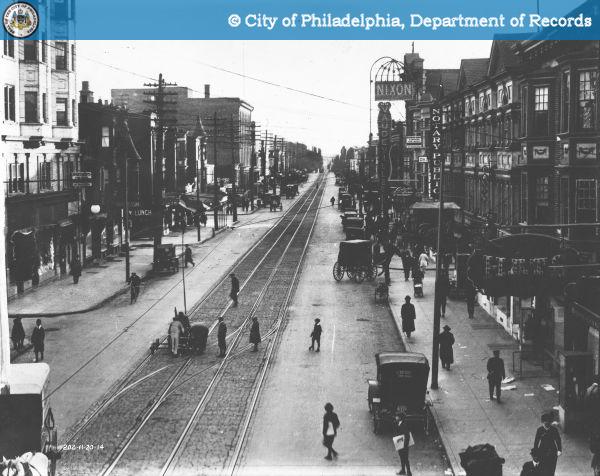

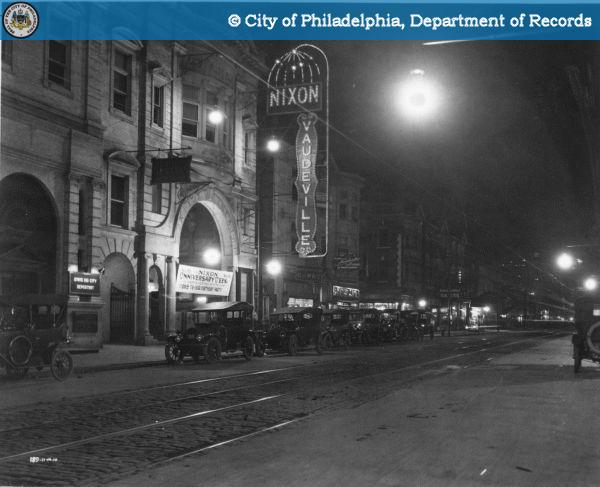

52nd Street in 1914, looking south from Market. Nixon Theatre

seen on right.

Nixon Theatre, 28 South 52nd Street, seen here in 1914.

Many of the neighborhood theatres were located in commercial corridors. West Philadelphia’s main street for well over a century has been 52nd Street. For much of its history, the Nixon Theatre lit up its night. Originally a vaudeville theater operating under a tent, the grand Nixon was built in 1910 near the head of the vibrant commercial strip. The 1,870 seat theater was designed by architect John D. Allen, who had recently designed the much more elaborate Orpheum Theatre on West Chelten Ave. Converted to film presentation in 1929, the Nixon operated until 1984.[ii] The brick and stone classical façade featured a two-story arched entrance, topped with a gentle bow window, and a prominent baroque split pediment.[iii] The site is now occupied by a nondescript building housing Payless ShoeSource and Rainbow Kids.

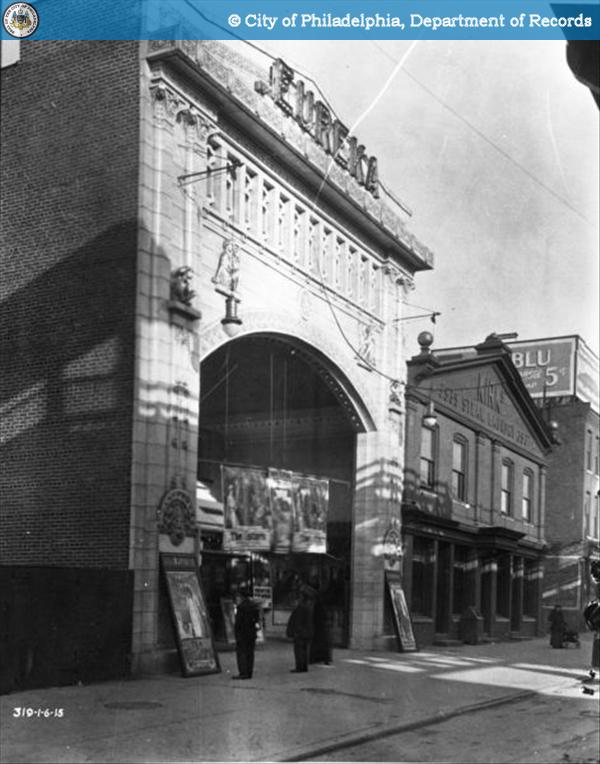

Eureka Theatre, 3941 Market Street, seen here in 1915.

Another eye-catching classically designed theatre in West Philadelphia was the Eureka Theatre. While the building had a much smaller capacity of 450 seats, the large terra cotta façade was designed to be seen from a fast moving train on the elevated Market Street line just feet away. Designed by Stearns and Castor, now best known for their Colonial Revival homes, the Eureka opened in 1913 and operated through the 1950s when it was converted into a furniture store.[iv] It was demolished in the 1970s to make way for the high-rise which is now the University Square retirement home.

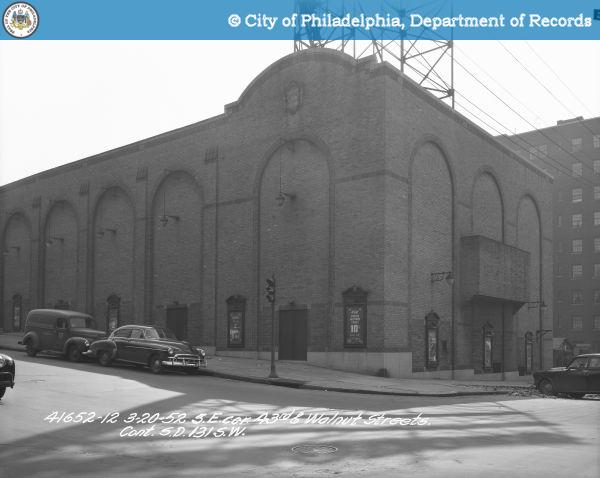

Commodore Theatre, SE corner of 43rd and Walnut, seen here

in 1952.

Many of the neighborhood theater buildings have survived but today serve other purposes. The 1,105 seat Commodore Theatre in Walnut Hill opened in 1928.[v] Designed by the Ballinger Co., the Moorish styled building was converted in to the Masjid Al-Jamia mosque in 1973. While the interior’s Moorish ornamentation was thematically appropriate for a mosque, much of it seems to have been removed.[vi] The theater was designed for film, but transitioned to legitimate theatre (with a thrust stage) in the 1960s for a few years before becoming the Miracle Revival Tabernacle church, prior to its use as a mosque. The large rooftop sign structure, now empty, was installed in the 1930s.

SOUTH PHILADELPHIA

Neighborhood theaters provided an air-conditioned respite from the grind of modern life. This is perhaps best represented by the fictional 1930s South Philadelphia Paloma Theater in the 1995 film, Two Bits. Twelve-year-old Gennaro spends the nearly whole film searching for two bits (a quarter) to see a film in his Mifflin Square neighborhood’s brand-new theatre.

Stratford Theatre, South 7th Street and Dickinson, seen here

in 1956.

Prior to the Paloma, Gennaro might have walked fifteen minutes north to Dickinson Street to see a film at the 600 seat Stratford Theatre. Opened as Herman’s in 1913, the theater became the Stratford in 1920 and showed movies into the 1960s when the building was acquired by the City and demolished for the parking lot that now occupies the site.[vii]

Broadway Theatre, South Broad and Snyder, seen here in 1931.

One of South Philadelphia’s largest and most popular theatres was the 2,183 seat Broadway Theatre. The building was built in 1913 as a vaudeville theatre to the designs of Albert Westover, a theatre architect whose office was in Keith’s Theatre Building at 11th and Chestnut. The theater was renovated in 1918 by Hoffman-Henon, the architects of the Boyd Theatre. The refined white brick and terra cotta Broadway was demolished in the 1970s for a drive-through restaurant. The site is now a parking lot for a Walgreen’s. [viii]

NORTH PHILADELPHIA

Great Northern Theatre, North Broad, Erie, and Germantown

Ave, seen here in 1925.

The 1,058 seat Great Northern Theatre was built on a triangular lot where Germantown Avenue crosses North Broad Street. This large theater had entrances on both streets with a lobby at the point facing northwest. A nickelodeon had been located here which was expanded in 1912. This photograph, looking northeast to the Broad Street elevation, shows the pronounced advertising of the silent film, the Sea Hawk. The theatre survived into the 1950s and was converted into a drug store in 1953. [ix] While the lobby portion was long ago demolished, the auditorium section of the building seems to have survived.

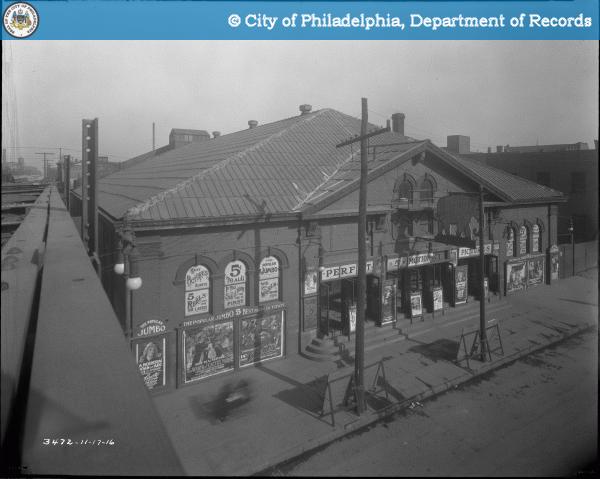

Jumbo Theatre, Front and Girard, seen here in 1916.

Also surviving as a shadow of its former self is the Jumbo Theatre. This 1,300 seat theatre was constructed in 1909 to the designs of Carl Berger and renovated in 1912 by Hoffman-Henon Co. [x] Seen here in 1916, the theater is covered with signs about its “5 cent reels.” Said to be one of the largest theaters in the city when it opened, it showed films into the 1960s. As evidenced by the huge elephant sign suspended over the front doors, the theater was named after the famous elephant that P.T. Barnum bought from the London Zoo in 1882. The elephant was given the name Jumbo by the zookeepers and through Barnum’s publicity machine, Jumbo became synonymous with “huge.” [xi] (Remember that the next time you order a jumbo popcorn at the movies!) Recently operated as “Global Thrift,” the façade had been insensitively covered. The building is currently being converted into a dollar store and the paneling has been removed, exposing the original ornamental brickwork. The proscenium arch inside had survived until this spring.

Ogontz Theatre, 6033 Ogontz Avenue, seen here in 1985.

The Ogontz Theatre was one of Philadelphia’s most beautiful neighborhood theatres. Located in the West Oak Lane neighborhood, the Ogontz was designed in the Spanish renaissance style by Magaziner, Eberhard, & Harris. This 1,777 seat theater opened in 1927, closed in the 1950s and was subjected to decades of neglect and vandalism prior to its 1988 demolition.[xii]

The Uptown Theatre, 2240 North Broad, Seen here in the 1970s.

The 2,146 seat Uptown was also designed by Magaziner, Eberhard, and Harris, and is considered one of their finest buildings. As described in the 1929 opening day program, the building is “an Exquisite expression of 20th Century art. Grace of line, delicacy of coloring, beauty of craftsmanship, and mystery of scintillating and reflecting surfaces.” Like many theatres of this period (the Boyd included) it was laid out for film more than vaudeville, and featured a narrow stage. Despite this, the theatre became a major center of Philadelphia’s African-American culture in the 1950s. It closed in 1978, briefly reopened in 1982, and is now the focus of an ambitious preservation effort by the Uptown Entertainment Development Corporation.[xiii]

Midway Theatre, Kensington & Allegheny, seen here in 1932.

The Midway Theatre opened in 1932 in the Kensington neighborhood.[xiv] It “was the last truly grand building of the motion-picture palace era in Philadelphia.”[xv] An art-deco show-stopper, the building could be seen down the avenue for blocks. The 2,727 seat theater was one of the largest theatres outside of Center City – and operated as a second-run theatre showing films that had already opened downtown. It survived into the 1970s and was demolished in 1979, following neighborhood opposition to plans to convert the building into a rock and roll venue.

Of the 468 movie theatres built in Philadelphia since the 1890s, 396 were located outside of Center City in the neighborhoods. As with the downtown theatres, the vast majority (more than 90%) of these buildings have been demolished, but they remain as vivid memories for many. These amazing photographs of both lost places serve as inspiration to those working to save theatres like the Boyd and the Uptown.

[i] As with the earlier blog post on movie theatres, most of the factual information in this piece has been culled from the work of Irvin Glazer (1922-1996) who documented the history of Philadelphia theaters in two books: Philadelphia Theaters: A Pictorial History (Dover Publications, 1994) and Philadelphia Theatres, A-Z: A Comprehensive, Descriptive, Record of 813 Theatres Constructed Since 1724 (Greenwood Press, 1986). His collection of photographs, clippings, and research files is housed at The Athenaeum of Philadelphia. Most of the photographs have been scanned and are available online in a format that permits zooming. http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/co_display.cfm/483480?CFID=60415619&CFTOKEN=31750787

[ii] NIXON: Glazer 1986, p.176; Glazer 1994, p.11; and http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/10327.

[iii] Images of the façade can be found here: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/image_gallery.cfm/7240.

[iv] EUREKA: Glazer 1986, p.108; Glazer 1994, p.22; http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/33645; and http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/5588.

[v] COMMODORE: Glazer 1986, p.90; Glazer 1994, p.55; http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/25802 ; and http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/5729.

[vi] As seen in the photographs in this Daily Pennsylvanian article: http://www.dailypennsylvanian.com/node/52658

[vii] STRATFORD: Glazer 1986, p.220-221; http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/10667; and http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/5340.

[viii] BROADWAY: Glazer 1986, p.74; Glazer 1994, p.16-17; http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/4912; and http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/5826.

[ix] GREAT NORTHERN: Glazer 1986, p.132; and http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/7293.

[x] JUMBO: Glazer 1987, p.141; http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/15280; and http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/6884

[xi] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jumbo

[xii] OGONTZ: Glazer 1986, p.178; Glazer 1994, p.48; http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/9070; and http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/16638.

[xiii] UPTOWN: Glazer 1986, pp.230-231; Glazer 1994, pp.60-65; http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/1807; http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/21193; and http://www.philadelphiauptowntheatre.org/.

[xiv] MIDWAY: Glazer 1986, p.170; Glazer 1994, pp.79-80; http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/9172; and http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/21351.

[xv] Glazer, 1994, p.79.